Okay, moving on....

Quite often, the undergraduate art history survey course is divided into two sections: Ancient and Medieval, and Renaissance and Modern. Renaissance means "rebirth," from the Latin renasci, "be born again." What exactly was this "rebirth"?

Understanding the Renaissance means understanding our present historical situation, as the Renaissance is generally identified by historians as the Early Modern period. Many cultural, social, religious, technological, scientific, historical, political, and economic structures of our contemporary society have their roots in this period. In art, it is both the standard bearer for great art, and what all artists have rebelled against. And while it is generally understood that all of Europe underwent this rebirth, this post will specifically deal with the Italian Renaissance, with later posts devoted to the equally interesting Northern Renaissance.

As with the survey course, we begin with discussing late medievalism because to understand what was reborn, we must understand what was left for dead. Medieval Europe is the period after the fall of Rome through the Renaissance, and is (unfairly) called the Dark Ages. For some historians, medieval Europe shows a stagnation of learning, incredibly low mortality rates, and an unfair socioeconomic/political structure known as feudalism. (It is also the period that brings us soaring Gothic cathedrals, beautiful illuminated manuscripts, and the formations of the present-day nations.) Furthermore, this "darkness" was seen in comparison to the perceived learning, light, and progressive nature of the ancient Greeks and Romans. Both the term "dark ages" and the idealization of Greco-Roman antiquity indicate how history can be manipulated through bias.

Anyways, late medieval art in Italy looks like this:

Bonaventura Berlinghieri, panel from the St. Francis altarpiece, 1235, tempera on wood,

Bonaventura Berlinghieri, panel from the St. Francis altarpiece, 1235, tempera on wood,5' x 3' x 6'. Church of San Francesco, Pescia.

Ancient Greek and Roman art looked like this:

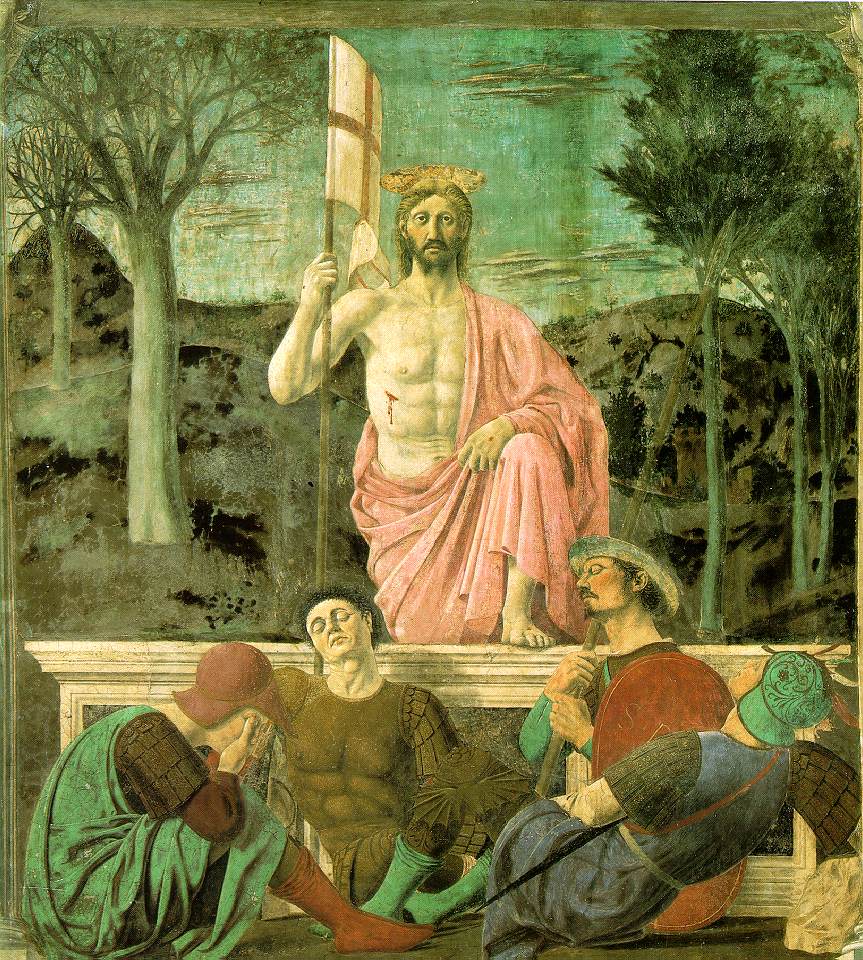

And Italian Renaissance art looks like this:

You can see from the naturalistic volume, idealized anatomy and proportions that Renaissance art looks a lot like ancient Greco-Roman art. Renaissance artists are credited with reviving the idealized and naturalistic forms of antiquity. This revival accompanied a general rebirth of the liberal arts for the aristocratic classes, an emerging middle class, vernacular Latin dialect, and the repopulation after the Black Death that reached Italy in 1348. (For the purposes of this post, the Renaissance took place 1400-1600 but I ask that you see these dates with some nuanced understanding. People didn't wake up on January 1, 1400 and say, "Well, now we're in a Renaissance! Lets start printing books and imitating the Greeks!" Rather, the developments that came into fruition during those dates had their roots in the late medieval period.)

Most importantly, a new mindset began to take place: humanism. Human-ism. I call it the "humans first!" ideology; humans begin to start questioning their own place in the world and through the accumulation of new knowledge, begin to theorize about individual potential. To slightly stereotype the medieval mindset, people were told by the main authority (the Church) that they were lowly, weak creatures who endure lives of pain and labor, and by the grace of God, if you were pious enough, you may reach the rapture of the heavenly afterlife. To slightly generalize the Renaissance mindset, people began to ask, "really? That's the way it has to be?'

For artists, there was a new interest in representing the world as the eye saw it, and an increased artistic drive to not only depict the real world, but to make it perfect. No longer do images need to flat and otherworldly but the can be, well, real. Beauty = truth; truth = perfection; ergo, beauty = perfection, another way to achieve heaven. Artists experimented with a variety of techniques and devices that craft a real-looking appearance: linear perspective and single-light source modeling. Significantly, we start seeing idealized proportions and anatomy: humans start to look like Greek (pagan) gods. Here, Jesus has taken on an appropriately idealized, godly form:

Piero della Francesca, Resurrection, 1463, mural in fresco and tempera, 7.38' x 6.56'.

Piero della Francesca, Resurrection, 1463, mural in fresco and tempera, 7.38' x 6.56'.Museo Civico, Sansepolcro, Italy.

And figures no longer stand stiffly. Bonaventura Berlingheri's St. Francis looks timeless, permanent; his body is concealed under his thick robe, his feet hover off the ground (only the blessed do that) and he exists in a heavenly gold world (achieved by the use of gold leaf). Piero della Francesca's Jesus looks like a proud man, and has returned to a world with realistic space, trees, and sleeping guards.

In the Italian Renaissance, sculptures exist in the same world and move the same way as humans. Here is Donatello's David, considered the first freestanding nude sculpture created since antiquity:

In the Italian Renaissance, sculptures exist in the same world and move the same way as humans. Here is Donatello's David, considered the first freestanding nude sculpture created since antiquity:

Donatello, David, c. 1444-46, bronze, approx. 5' high. Museo Nazionale del Bargello, Florence.

David stands in contrapposto ("counter pose"), shifting his body weight onto one leg as he contemplates Goliath's head at his feet. Contrapposto creates a beautiful harmony of opposites: one bent leg across from a straight arm, a straight leg opposite a bent arm. It is how humans stand and move through the world, letting gravity pull weight onto one leg and to compensate, the other leg bends. Art is no longer reserved for the holy and righteous; Donatello's David's small shift of the body brings the world of art back to the world of man. Hence, rebirth.

No comments:

Post a Comment